Could Rising Seas Force The Bay Area To Solve Its Housing Crisis?

The Mega Margins project envisions a planned retreat from the shoreline—and using the emergency to break the deadlock about development in San Francisco.

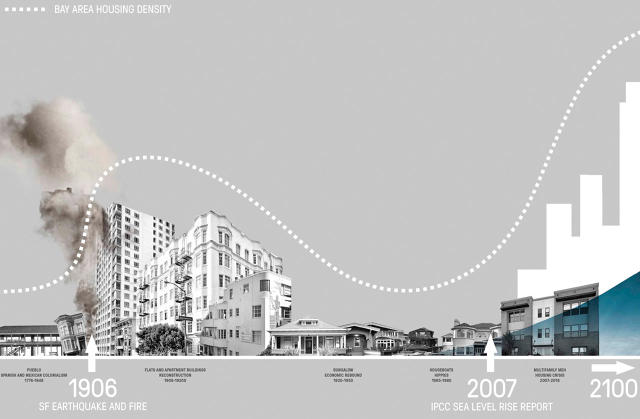

When a massive earthquake and fire leveled San Francisco neighborhoods in 1906, developers used the disaster to circumvent red tape and build much denser housing than before. Now a team of designers thinks that an impending disaster—sea level rise—can help the Bay Area solve its current housing crisis in a similar way.

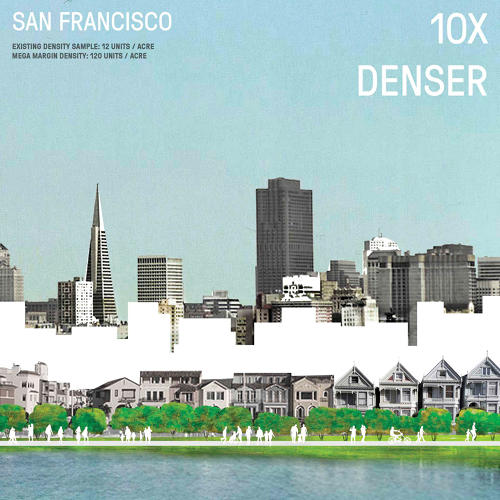

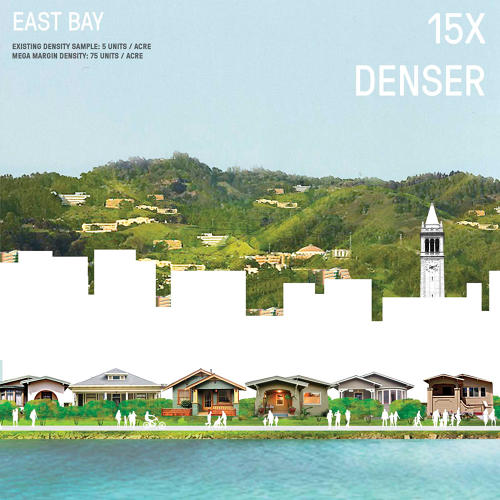

In a new speculative design called “Mega Margin,” they map out how neighborhoods bordering the waterfront could retreat from rising water, with new parks at the water’s edge. A ring of new buildings, safely set back, would be built to house many more people than a typical block in San Francisco, Berkeley, or San Mateo currently holds.

“The Mega Margin targets an area that will inevitably need to change in response to sea level rise,” says designer Emily Schlickman, who worked on the project with Anya Domlesky at XL, a new innovation lab at the Bay Area-based design firm SWA.

At the firm’s offices, in the waterfront town of Sausalito, flooding is already a problem in the winter, innudating bike paths, bridges, and parking lots. “Last winter we got a glimpse of what the future of sea level rise could look like,” says Schlickman.

The architects realized that the slow-moving disaster of sea level rise—which threatens $77 billion worth of property in San Francisco alone—is, by necessity, forcing cities to redesign neighborhoods that border the bay. That need could solve another problem facing the area: There isn’t enough housing to meet demand, but anti-growth politics make it challenging to build more.

“This project takes two seemingly intractable issues—sea level rise and the housing crisis—and thinks about a way to confront each that is not doom and gloom,” says Domlesky. “There are pathways forward. We want to push people to rethink the city they live in, what the region has become today, and what it could be tomorrow.”

Along the bay, the Mega Margin uses natural space and parks as a buffer. “We wanted to explore how managed retreat could be an alternative to traditional engineering solutions that tend to favor hard infrastructure over soft,” says Schlickman. “By relocating some buildings upland, the potential for catastrophic loss due to sea level rise can be reduced. Also, by adapting to a new shoreline and creating a resilient public space capable of inundation, we can design for even more densification.”

In the design, the designers modeled how much denser the ring of new housing could be. In San Francisco, where some existing neighborhoods have 12 housing units per acre, the Mega Margin would have 120 units per acre. In Marin, density would move from 7 units an acre to 35. In the South Bay, where sprawling suburban homes are the norm, the new ring of development would be 100 times denser than a typical neighborhood.

The design is a regional solution, focused on the whole Bay Area rather than a particular city. The area is beginning to focus on regional planning—Measure AA, which recently passed, takes taxes from nine counties to fund sea level rise mitigation. The architects think more regional planning will be necessary.

“Commonly, governance has been at a local level,” says Domlesky. “This clearly won’t work with the large-scale environmental changes that are taking place—wildfire, sea level rise, air and ocean warming will impact at the scale of regions and ecosystems, not towns.” The housing crisis, too, makes sense to solve as a regional problem, not something that solely faces San Francisco or other cities alone.

The designers plan to pursue the idea. “While ambitious, in the future we hope to see parts of our proposal adopted,” Domlesky says.

Have something to say about this article? You can email us and let us know. If it’s interesting and thoughtful, we may publish your response.