Urban Parks: From Dumping Grounds to Centers of Energy

A major initiative by New York City Parks Commissioner Mitchell J. Silver cogently explored at the recent and fascinating Parks Without Borders Summit is to make parks more porous and accessible and, by extension, to foster park equity, the idea that all parks are well maintained.

“The goal of the Parks Without Borders initiative is to make “parks more open, welcoming, and beautiful by improving entrances, edges, and park-adjacent spaces.”

This comes during one of the most exciting periods in modern urban history in which parks have gone from being dumping grounds, perceived as dangerous, to centers of energy. This renaissance has been brought about by forward-thinking municipal officials, public-private partnerships such as the Central Park Conservancy and the Prospect Park Alliance, along with the support and advocacy of New Yorkers for Parks, the New York Restoration Project, the Trust for Public Land, and other savvy, resourceful, and entrepreneurial groups.

Add to this richness Brooklyn Bridge Park by Michael Van Valkenburgh Associates and Governor’s Island by West 8 (the next phase of the latter – an ambitious and astounding project called “The Hills” – opens in July), along with other projects, and the picture in the Big Apple is impressive.

But when it comes to New York parks, the concept of porosity is not altogether new. Ninety years ago the Central Park Association, organized to “stimulate and aid the City of New York to restore Central Park to life and vigor,” enlisted prominent citizens to promote access to the park through various stone gates along the its perimeter.

The chairman for the “Hunters’ Gate” on West 79th was Theodore Roosevelt, while efforts for the “Women’s Gate” were led by Edna Ferber, and others.

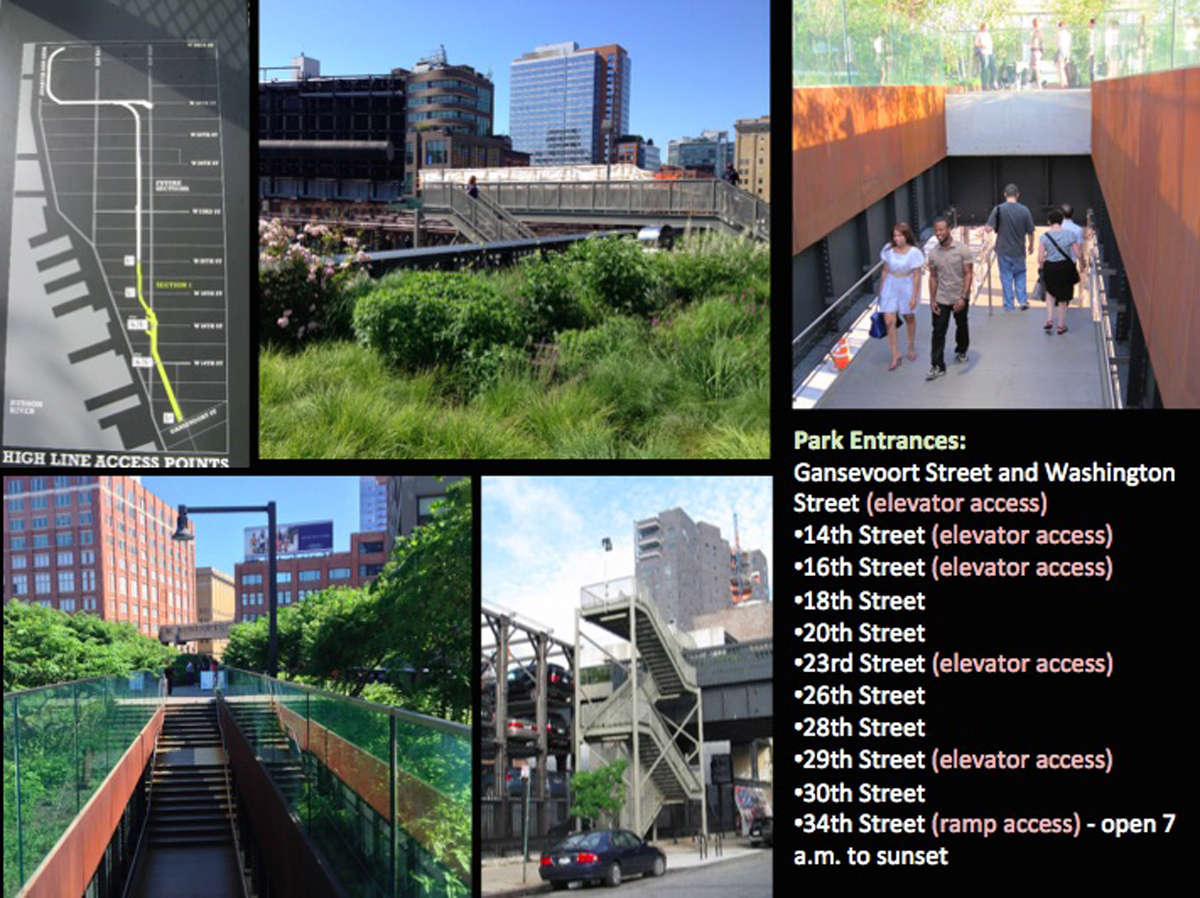

There are twenty entrances along the edges of the 843-acre park; by contrast, there are eleven entrances to the vastly smaller High Line.

While Commissioner Silver’s Parks Without Borders Summit focused on New York City’s five boroughs, issues of park porosity, connectivity, and accessibility are being raised across the country. In fact, as the value of parks new and old is rediscovered, demand for increased access (both visual and physical) has also grown considerably. As I told the Summit’s sold-out crowd convened at the New School, access to parks in Chicago, Dallas, San Francisco, and other urban centers is increasing, as the parks are becoming more porous (breaking the edges) and as new networks and systems are created, and sites are capped (building over roadways and similar infrastructure).

In New York, the rehabilitation of Bryant Park, just blocks from Time Square, was a significant milestone when it reopened in 1992. Landscape architect Laurie Olin’s surgically precise design has created a stage for a broad range of programs and events.

In Los Angeles, the work by Rios Clementi Hale is transforming Grand Park, a formidable site, through new pedestrian circulation patterns, improved access for those not able bodied, expansive sight lines and enhanced signage. And, visitors can even play in the fountain’s basin.

Discovery Green in Houston, however, is perhaps one of the more radical and successful interventions. Mary Margaret Jones at Hargreaves Associates has re-engineered a bland ten-acre expanse of surface parking fronting the city’s convention center into a verdant and vibrant park, one that is attracting families with children, and spurring construction along its borders (which the designers are responding to with new entry points).

Several major parks systems, notably Boston’s Emerald Necklace, arguably a future World Heritage Site, and the Louisville Olmsted parks, are overcoming the effects of poor stewardship decisions made decades ago. In Boston, a vital connection for the entire park system that for decades had been given over to vehicular parking, has been reclaimed.

One of the most exciting, and without question popular, is the work along Chicago’s riverfront by Gina Ford at Sasaki Associates (note: Ford is a TCLF Board member). With street-level entries down to the river, and the creation of pedestrian-friendly dock-like structures along the water’s edge with raked seating, the design offers flexible events spaces, places for kayaking, and boat launches – all representing new and dramatic opportunities for interaction with the city.

Houston’s Buffalo Bayou Park by the SWA Group is the realization of a century-old idea to create paths and passageways along the bayou. For the automobile-centric city, the re-emergence of Houston’s seminal feature to include a network of paths that connect the Bayou—as a shared civic amenity — with its contiguous neighborhoods and infrastructure that blurs the line between art, landscape architecture and architecture is nothing short of revolutionary.

Capping roadways as Lawrence Halprin did in 1976 with Seattle’s Freeway Park has proved not only viable, but has helped close old wounds created when highway projects violently severed neighborhoods. The concept underlying Halprin’s pioneering masterwork has taken hold in Dallas with Klyde Warren Park by The Office of James Burnett.

Here, the aggressive and original programming by the non-profit that operates the park has solidified it as a local must-see destination; and the park has also knit back together sections of downtown and the arts district. Additionally, The Presidio in San Francisco is burying a set of roadways and building a thirteen-acre park above it, while back in New York City, dlandstudio has proposed a park over a portion of the Brooklyn Queens Expressway, a 1950s-era project by Robert Moses that not only created a gash through an established neighborhood, its presence has been associated with elevated asthma rates. The proposal would create new park space in an area that desperately needs it.

When Commissioner Silver and I discussed his Parks Without Borders initiative more than a year ago, I recognized it as a logical step in the evolution of the city’s parks. What was fascinating to learn was the intense public interest. In tandem with the summit, the city held a contest to determine which eight parks would receive funding towards rehabilitation that created greater access and openness. According to the city’s website, they received more than “6,100 suggestions for improving 692 parks, which is more than a third of all the parks and playgrounds in the city.”

The increased demand is also resulting in increased engagement. The top down dictates that scarred New York and other cities nationwide are being replaced by bottom up, community oriented decisions made with the benefit of forward thinking municipal leadership and leading landscape architects.

This article originally appeared in the Huffington Post on June 27, 2016.